Kayla Blanche, once a history teacher, remembered standing in front of her class as officials carted off every banned book from the library. She did not stop them. She wanted to, but couldn’t. The kids never saw her cry, but at night, she did. But she tore pages of truth and wrote on scraps of paper, tucking them into her coat. Among them were volumes of poetry, mysticism, and law, her favorites. The works of Aristotle, Plato, Cicero, Voltaire, David Hume, John Locke, and others, who she felt had accomplished the heroism of incarnation, taking on a human form and all of the baggage that comes with it as a divine act of sacrifice, redemption, or salvation.

Yet before the soldiers reached her classroom, she smuggled away a battered text wrapped in cloth: The Book of the Law. For Kaylah, that book was crucial. It was a torch against tyranny. Its creed, Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law, was not license for chaos but a declaration that every soul carried its own star, sovereign and inviolable. To live freely and fight for the freedom of all people was not indulgence, but duty. To deny freedom, or to enforce obedience by fear, was considered the greatest blasphemy.

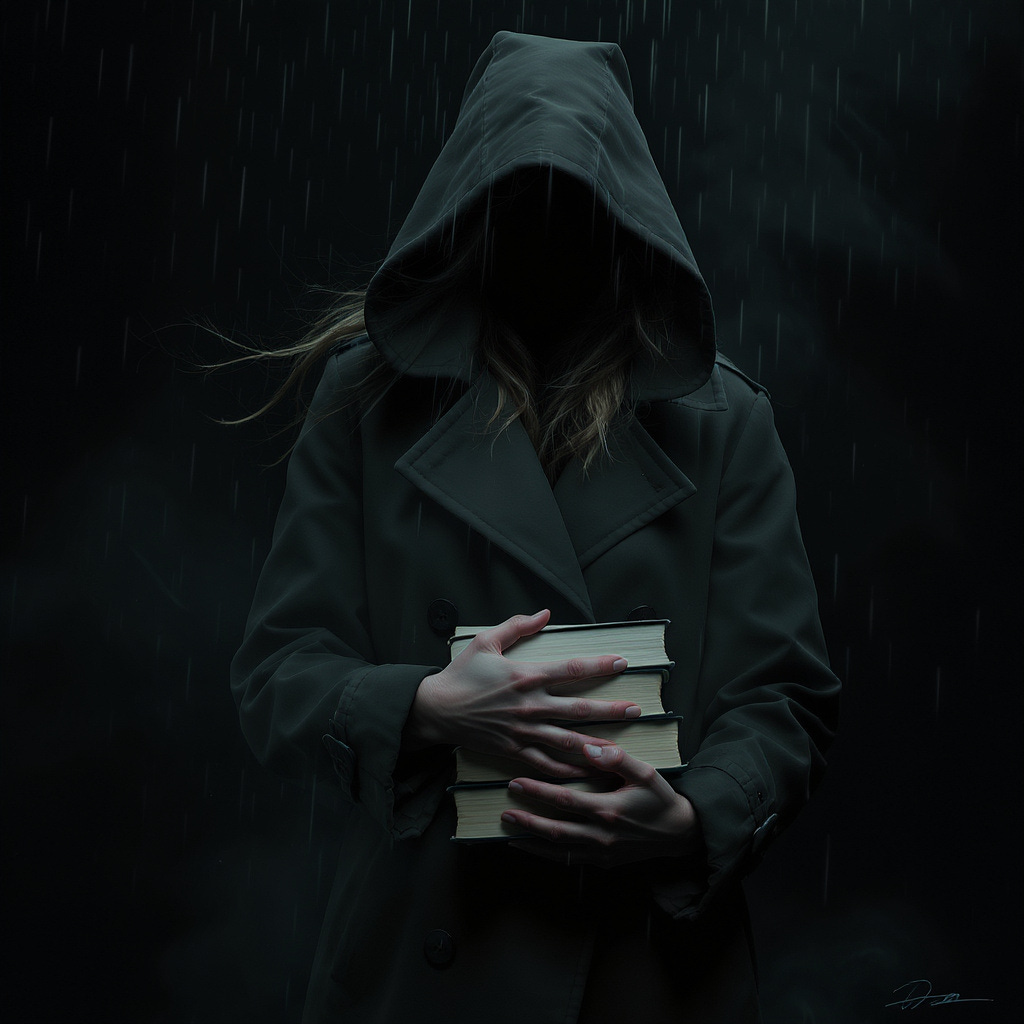

She has long, angular features that appear prematurely aged. Her eyes are gray-blue, sharp when she teaches, but often clouded with fatigue when alone. She’s tall but slightly stooped from years of teaching and carrying too much on her shoulders. Her once-neat clothes are now patched, though she keeps her coat in surprisingly good condition; the pockets are where she hides her contraband scraps of truth. Her hair is silvering, her glasses cracked but functional. Her hands are ink-stained, and her nails often carry traces of chalk or paper dust.

She has a tell when she is nervous. She’ll run her fingers across the edges of paper compulsively, and sometimes speaks in half-lectures, as if still in front of a class. When she’s about to say something dangerous, she lowers her voice into a conspiratorial murmur, leaning in as if history itself were listening.

She believes her superpowers include a talent for hiding things in plain sight, cryptic writing, and disguising truths in allegories, poems, and riddles. Speaks with quiet conviction that inspires trust in those who listen closely. She is motivated by preserving truth against censorship, passing on knowledge to future generations, and resisting tyranny through memory and meaning.

Kaylah is a gentle soul, thoughtful, burdened by guilt, yet quietly brave. She possessed encyclopedic knowledge of history, particularly in the areas of resistance movements and suppressed cultures, and this meant she should have known better, to do more.

She despises violence but keeps a handgun in her desk drawer “just in case.” She believes in free will, but sometimes subtly manipulates students, steering them toward “dangerous” texts to spark their curiosity. She thinks of herself as weak, yet others quietly regard her as a pillar. Students and strangers alike feel that she sees them as individuals, not tools or subjects. This makes her dangerous; she awakens others’ sense of self.

Kaylah is not the loud revolutionary, but the quiet keeper of fire. Her work is slow and invisible, but no revolution survives without memory and myth. She is not a fiery leader, but a woman of conscience whose quiet persistence makes her a formidable threat to a regime built on fear. She believes in teaching as a sacred act and feels deep regret for not standing up when the books were taken, but sees her small acts of preservation as a form of redemption. Some of her students still secretly visit her, carrying fragments of torn pages from banned books. They see her as a mentor, though she tries to keep them safe by pushing them away.

The officials who confiscated the books don’t see her as dangerous yet, but the survival of The Book of the Law and her growing underground reputation could change that. She doesn’t believe she will see the country restored in her lifetime, but she is planting seeds in young minds with the finesse of a spider spinning a web. At her core, Kaylah is not a warrior, but a gardener, a caretaker of seeds, intellectual, spiritual, and human. She does not fight tyranny with guns or speeches, but with memory, mentorship, and the stubborn act of keeping a book alive; however, she is beginning to believe this is no longer enough.

Next: The Cellar Meeting